Nyege Nyege at 10: Where the Underground Rises by the Nile

From sonic migrations to micro-enterprises, Uganda’s most iconic festival is shaping a new cultural economy. One beat, one hustle, one decade at a time.

By Samuel Okocha, On-ground Reporting – Kalagala Falls, Uganda

Music pulls crowds by the thousands to Nyege Nyege. But the first thing you notice at the festival isn’t the sound. It’s the movement.

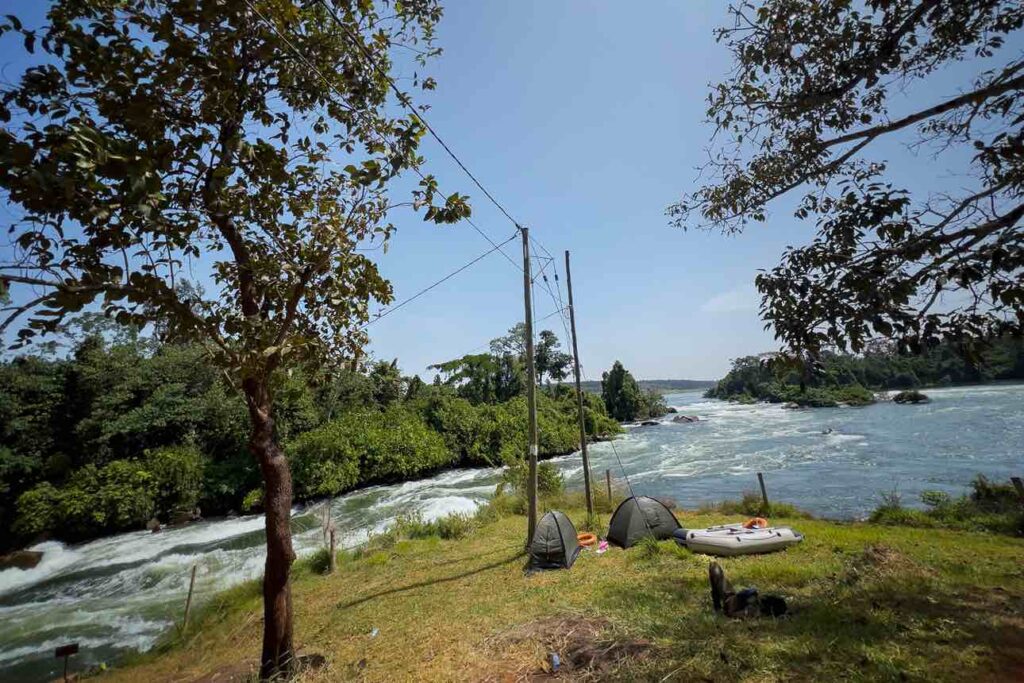

Artists hauling equipment across the forest paths of Kalagala Falls, vendors chopping food items behind zinc and wooden counters, festival goers drifting between stages carved into thick greenery, and the Nile itself roaring beside it all like an ancient metronome.

From November 20–23, 2025, Uganda’s most famous countercultural gathering turned ten. And in that decade, Nyege Nyege has grown from what co-founder Derek Debru calls “an act of madness” into a Pan-African nexus where underground creators converge, collaborate, and often return home with entirely new sonic identities.

I spent two days on the ground interviewing co-organisers, vendors, and workers who have since become the quiet engine behind the big event. This is the festival through their voices.

A Decade of Madness and Method

“We started this in an act of madness,” Derek tells me, smiling with some sense of nostalgia as I adjust my audio recorder.

He’s one of the original architects of the Nyege movement: an artist incubator, community studio, two record labels, a touring agency, and eventually, a festival.

But his real mission is clearer:

“We want to challenge the idea of what African music is.”

For Derek, the label “African music” is as limiting as it is inaccurate.

“How do you describe a continent that has 54 countries and Uganda alone has over 50 tribes? There’s no ‘Asian music.’ There’s no ‘European music.’ So why do we insist on boxing Africa?”

This year’s lineup featured over 300 artists. Most of them names you’ve never heard. And that’s deliberate.

“We have to get out of this headline mentality. The mainstream always steals from the underground. What we do is bring the underground to the front before the world comes to take from it.”

The programming reflects this philosophy: country music from East Africa, techno from Kampala, Lagos street beats (Trench), traditional sounds, experimental electronic genres, and everything in between.

The result? A sonic geography where Lagos meets Dar es Salaam, where Durban meets Gulu, and where no one feels out of place.

A New Home by the Falls

This year’s edition debuted a new site, Kalagala Falls, after several years of displacement due to COVID-19, relocations, and logistical challenges.

“It looks more like our original site,” Derek says. “Closer to nature. Iconic. Safe.”

And just as importantly, it allowed Nyege Nyege to deepen its collaborative DNA.

Fashion from Quetto Kwanzaa, film from Matatu Film Festival, programming from Ubuntu Stage, and a newly launched African Electronic Music Conference brought collectives from Nigeria, Ghana, South Africa, Côte d’Ivoire, Ethiopia, Kenya, and more.

The goal remains simple, with roots in cross-pollination.

“A kid from Lagos hears Tanzanian beats. South Africans hear the Lagos Trench sound. Suddenly everyone realises they’re playing the same vibe.”

Pan-Africanism in decibels, Derek adds.

Tourism, Culture & the Global Gaze

Nyege Nyege wasn’t created as a tourism product.

“It was never meant as a destination festival,” Derek insists. “It’s not made for foreigners to come and see what we do. It is made for this East African community to connect and realise all the different talents that are there.”

But with features in The New York Times, CNN, Le Monde, and BBC, the global gaze is unavoidable.

“I think it’s that authenticity that really draws people.”

A couple traveled “all the way from California just to experience it,” he tells me. Later, I spot them near the charging station, where I’d gone to power up my phone. “But they don’t come here to hear Californian music. They come because it’s authentic.”

The festival is now one of the strongest cultural tourism magnets in East Africa. And the numbers prove it.

A government-commissioned study estimates $3–4 million USD in direct and indirect economic impact annually.

The irony? Nyege Nyege itself has never made a profit.

“It brings millions to the economy,” Derek says. “But the festival still loses money. So is it unprofitable? It depends on who you ask.”

Voices From the Ground: The Vendors Who Keep the Festival Alive

But while the headlines focus on global reach, the festival’s heartbeat lives in the hands of those who build it. One plate, one plug, one performance at a time.

Vincent, “The Meat Guy” – Uganda

(Pork & grilled meat vendor)

For Vincent, Nyege Nyege has gone beyond a festival to becoming a lifeline.

“If this event is not here, my business struggles. When it is here, my business boosts.”

He depends on his stall—The Meat Guy—for daily income throughout the festival.

He speaks about networking with unexpected pride.

“Now I know you,” he says with a chuckle. “Next year I see you, I won’t pass you.”

But this year, he’s worried. Crowds appeared smaller than expected on Day Two.

“I invested a lot. This is not the crowd I expected.”

Still, he hopes the unfolding night and final day will turn things around. Festivals can be unpredictable, and survival, for vendors like Vincent, depends on optimism.

Frezia Bagenzi, “The Phone Charger”

(Phone charging station operator)

If Vincent is cautiously hopeful, Frezia is beaming.

“This year is special. The turnout is high. We are making money.”

Her charging rack—a secure, lockable system she designed after studying past editions—is in constant demand at camping festivals.

She attended her first Nyege Nyege in 2022 as a fun-seeker. Then she saw an opportunity.

“People love fun, but they suffer. No place to charge. So I found a better solution—safe charging, even when it rains.”

She charges phones while enjoying the music herself. A side hustle with a rhythm of its own.

Unlike Vincent, this is her most profitable edition yet.

“It is international now. People from abroad, from East Africa, from West Africa—all here. We enjoy and make money.”

For her, Nyege Nyege isn’t just a festival. It has become a classroom in entrepreneurship.

In the Wake of Music: A Cultural Economy Unfolds

From incubating artists to elevating micro-businesses, Nyege Nyege sits at the intersection of tourism, culture, and a fast-evolving African music identity.

Derek dreams of a future where:

• the festival becomes multi-country,

• African electronic creators get more global stages,

• and the cultural sector creates sustainable jobs.

“The model is somewhere there,” he says. “It just needs time.”